Re-shaping our understanding of political violence and conflict

Clionadh Raleigh, Professor of Political Geography and Conflict at the ÄûÃÊÊÓƵ, has spent the past eight years collecting data related to violent incidents in order to re-shape the way we understand political violence and conflict. The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) she set up in 2014 now has nearly 200 staff mapping political violence across the globe.

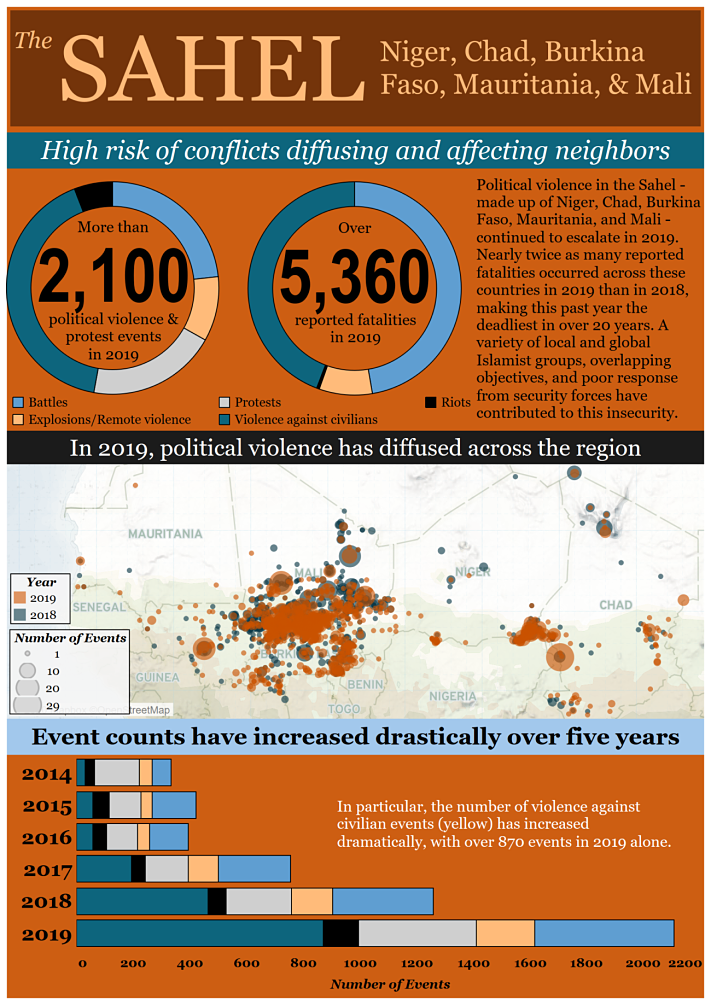

“The Sahel conflict incorporates quite a number of worrying trends. …Both Al Qaeda and Isis have found a home there and have co-opted groups that operate there sub-nationally – they fight the government, the international community, they are currently fighting with each other and that conflict shows no sign of stopping,” says , Professor of Political Geography and Conflict at the ÄûÃÊÊÓƵ.

Raleigh is referring to an explosion of violence since 2012 in west African countries, such as Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, where Jihadist groups, having lost ground in the Middle East, are now expanding. “The Sahel conflict gets portrayed as a perfect storm. But it’s not,” said Raleigh. “You can see it coming. But because they are transnational and quite large conflicts incorporating threads and scales of politics and violence, it becomes hard for one country or one president or one organisation to stop these trends. An absolute disaster is going to occur there once that seeps into northern Nigeria, which is already rife with internal conflicts, or Benin, or the Ivory Coast.”

Given that Raleigh has spent the past eight years collecting data and insights about the causes of political violence across African states, she should know. Raleigh started to examine the causes of political violence within and across African states as part of her PhD work, and began expanding this work in 2012 through a £1 million grant from the .

By providing detailed evidence from conflicts, Raleigh aimed to challenge what she refers to as “dominant and mistaken” theories of conflict. Theories that conflicts don’t occur in democratic countries, that they’re a sign of state failure or state capacity, or that they’re due to poverty and inequality are some of the misconceptions Raleigh aims to challenge through evidence. “All of these are tautological explanations,” she says. “Yes, we see lots of violent conflict in poor countries, but it’s not because of poor people. This is often the mistake – of assuming it is so.”

was registered as a non-profit organisation in 2014 in America, with Raleigh as the Founder and Executive Director. It has grown enormously since then, and now has almost 200 staff mapping political violence in Africa, South Asia, Southeast Asia, East Asia, Central Asia, the Middle East, Europe, and Latin America, with North America soon to be added to its list. Its primary funders are the U.S. Department of State, the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the German Federal Foreign Office, but it also receives financial support from other groups such as the International Organization for Migration. How does Raleigh explain the rapid growth and success of ACLED? “There was a niche to fill and we have done it very well.”

Highly credible and widely used by analysts, its data and analysis is freely available for public use. ACLED’s Sahel conflict data shows how recent conflicts in Nigeria and Mali, often described as ethnic or religious clashes, are fundamentally driven by political issues, such as access to resources. It , which shows how Jihadist groups have been adept at exploiting local grievances and power structures in Mali and Burkina Faso to gain access to hundreds of artisanal gold mines. The Sahel region’s unregulated gold trade is estimated to be worth around 2 billion dollars.

Major media outlets, including the BBC, The Economist, The Financial Times and The New York Times are making substantial use of the Sahel data, which has also been cited in a , and , and has been used by a range of think tanks. From January 2018 to June 2020 alone, ACLED data was referenced by the global media an average of more than 655 times per month.

Making sense of Sierra Leone’s civil war

Raleigh began to see the importance of local politics and power in shaping conflicts in 2015, when working closely with researcher Kars De Bruijne to analyse detailed data he had compiled related to Sierra Leone’s civil war, which lasted from 1991 to 2001. The data included details such as where violent acts took place, and how intense and frequent they were. “We’d been told: there is a government and a rebel group and they are fighting, and sometimes they kill civilians”, said Raleigh. “Once we started to look at data from local non-governmental organisations and local media, the conflict started to look very different.”

that violence in Sierra Leone’s civil war was shaped by local politics and the power of local authorities, such as tribal chiefs. Armed groups unsurprisingly established themselves in areas with “weak, co-opted local authorities” that showed promise for generating wealth. “We found that there are often dozens of groups on either side conducting lots of violence in different spaces. Violence is a competition for power – not a vacuum.”

Getting the ‘view on the ground’ of a conflict

ACLED has continued to develop an understanding of local conflicts in countries by building up a network of researchers, often based in the countries they are reporting from. The researchers track events reported by local partners, local and international media coverage, NGO, government and UN reports to provide timely data, which is published at the start of every week. “The cornerstone of our data collection network and our methodology is our local partners and conflict observatories that we work with around the world to get the view on the ground,” said Sam Jones, Communications Manager for ACLED.

“At a time when there is an effort to automate this work, by trawling the internet and scraping media by using Artificial Intelligence and that sort of thing, our belief is that tends to miss a lot and tends to create errors or to exacerbate biases,” said Jones. “You really need a global human network to include a level of judgement and review. That sets our data apart.”

“We are no longer a small fish”

ACLED’s data directly informs the decision-making of national, international and transnational governmental organisations, and a range of foreign aid strategies and budgets. “We are no longer a small fish. We are now a reference point for governments, for the African Union, for the United Nations, for the World Bank etc,” said Raleigh.

ACLED data often reveals realities that forces international organisations to re-think their policies and analysis of conflict areas. “When ACLED says a fact, then larger external organisations – like the US government, the UN – have to respond to this external fact that we have dropped into the conversation. That’s a unique position to be in.”

ACLED’s real-time monitoring of the conflict in Yemen helped to expose the real cost of the war in the absence of regularly updated death tolls from UN or government sources. While official sources indicated the casualty total stood at 10,000 for years, ACLED released data showing the figure was likely to be over 50,000 as of 2018. The reported death toll has since to more than 100,000 as of 2020, including more than 12,000 civilians killed in targeted attacks.

Speaking out against America’s role in the Yemen war, , while Jeremy Hunt, UK Foreign Secretary from 2018 to 2019, referred to it in Tweets calling all parties to support the UN envoy’s talks. The data was also referenced by , the , the , the , the , the , and a range of non-governmental organisations and the media.

Analysing African governance and the political elite

Raleigh contends that many conflict researchers “remove all the politics from studying any conflict”. Her new African Cabinet and Political Elite Dataset (ACPED) project, launched in 2017, aims to rectify that by providing analysis of governance in Africa. It’s tracked each minister in every African cabinet for the past 20 years and is now compiling and releasing data on cabinets for 23 states, including each minister, their characteristics, such as gender, ministry and which political, ethnic, regional and the party groups they represent.

African regimes are frequently characterised by high and sustained levels of ethnic and regional inclusion in cabinets. This directly contradicts prevailing views that regimes are politically exclusive. But even where there is a high level of inclusion, regimes still experience high rates of conflict, often driven by militias hired by powerful political elites. Their conclusion? Being politically inclusive does not create peace.

Raleigh paints a bleak picture of elites driving political change – not civilian pressure or collective action. “Domestic politics of all countries, but in particular developing countries, is highly contentious and competitive. Elites are using violence as a way to compete with each other,” said Raleigh. “Rather than seeing this as a state failure or a bug in the system, we should see it as a feature of the system. The corruption, the violence and the state capture [of resources] is a function of this elite political competition that we see.”

Raleigh hopes these more accurate narratives will open up new avenues of investigation, lobbying, political scrutiny and accountability. “If we can provide detailed assessments of what’s happening, then that will allow people to advocate for policies that are based on the evidence.”

Contact us

Research development enquiries:

researchexternal@sussex.ac.uk

Research impact enquiries:

rqi@sussex.ac.uk

Research governance enquiries:

rgoffice@sussex.ac.uk

Doctoral study enquiries:

doctoralschool@sussex.ac.uk

Undergraduate research enquiries:

undergraduate-research@sussex.ac.uk

General press enquiries:

press@sussex.ac.uk